Time for a balance between passion and pragmatism

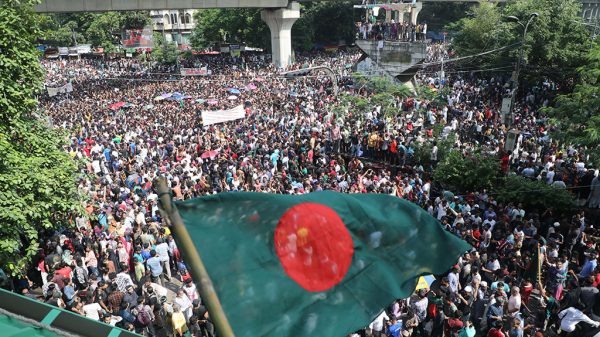

THE dramatic fall of the authoritarian Awami League regime, driven by the unyielding energy and vision of Gen Z, marks a watershed moment in Bangladesh’s history. Like many, I have been both a witness to and an active supporter of this transformative movement, marvelling at how young students, popularly referred to as Generation Z, have ignited the entire nation with their fervour and dedication to justice. With the initial triumph now a reality, it is time to turn our gaze towards the horizon. The true challenge lies in steering this momentum towards enduring state reforms, forging political consensus, and achieving genuine national reconciliation.

Any movement typically begins with an intense burst of energy and enthusiasm. However, as it evolves from a protest movement into a force for state reform, it becomes increasingly crucial to infuse it with wisdom, realism, and pragmatism. This shift is essential for pursuing the broader objectives of the movement in a sustainable and effective manner.

One of the most critical challenges facing the popular anti-discrimination student movement is the risk of alienating potential allies. In any movement, leadership should not become a point of contention, nor should there be competition for credit for its success. Every citizen, both within the country and abroad—excluding those directly complicit with the Hasina regime—is an equal stakeholder in this movement. While political parties have genuinely attributed the triumph to young students, regardless of their political affiliation, and acknowledged their sacrifices, some student leaders appear to be disregarding the wisdom and experience of senior politicians and the contributions of political parties. This attitude, seemingly rooted in frustration over the political parties’ failure to topple the autocratic regime despite years of effort, is counterproductive and undesirable. Political parties and senior politicians with decades of experience navigating the complexities of governance and administration should not be undervalued. Their wisdom and experience can provide invaluable insights that help avoid pitfalls and guide the movement towards sustainable success.

We must remember that a revolution or a mass uprising is never an overnight occurrence; it requires a prolonged buildup of circumstances. Prior to Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, the people of East Pakistan endured 23 years of systematic exploitation and oppression under the West Pakistani rule. This prolonged suffering fuelled deep-seated resentment and frustration among the populace, which eventually erupted into a mass movement. The ordinary people, driven by their desire for freedom, risked their lives and joined the struggle, ultimately achieving independence. Similarly, the foundation of the July uprising was laid over the last 16 years. Throughout this period, opposition political parties have faced brutal political repression as they protested against the Hasina regime’s vote rigging, corruption, and numerous irregularities — a truth that cannot be ignored.

The emergence of a new political party from such a successful student movement is both natural and expected, though it will take time to materialise. This may explain why young student leaders have initially advocated for extending the interim government’s tenure to 3–6 years, alongside the nation’s urgent need for institutional reforms. Establishing a political party that can resonate with grassroots voters and compete on a national scale is a formidable challenge. In the current context, students may continue to act as vigilant watchdogs against discrimination and by monitoring the reform process and state governance, rather than prematurely shifting their focus to political ambitions.

Student leaders are still indecisive as to whether student politics should continue in academic institutions. Some argue in favour, others against, while a third group suggests that only non-partisan student politics should be allowed. But who will have the authority to decide what qualifies as non-partisan? Is there a clear standard to define it? And if such a standard is established, will all student organisations agree to and abide by it? Without a platform for student politics, any political party emerging from the anti-discrimination student movement might struggle to gain traction as a popular political force. Lacking the opportunity to cultivate a base of supporters within educational institutions, the student movement could find it challenging to disseminate their political ideals and values on a national scale. This, in turn, could lead to a rapid decline in their political relevance and influence. On the flip side, if student politics continues and a political party arises from the anti-discrimination student movement, it could ironically transform the very movement into yet another partisan student organisation—the type of entity that student leaders have been vehemently opposing. This scenario would create a striking paradox and highlight a profound contradiction.

Electoral politics is a different phenomenon from street movements, and a distinction should be made between the two. While the latter can bring about change, the former is essential for consolidating and institutionalising the change. Both play complementary roles in achieving and sustaining reform. The influence of mainstream political parties and their electoral symbols at the grassroots level is not established overnight. The influence is deeply rooted and is the result of decades of sustained grassroots engagement and representation, which are essential for earning broad-based support. Even if a political party successfully emerges from within the movement, it will take decades to popularise and embed it at the grassroots level. A potentially new political party, led by Gen Z student leaders, might secure some electoral seats in large city centres, where educational institutions are highly concentrated. Yet, performing well electorally outside the urban centres will be challenging. Additionally, the challenge of competing against seasoned politicians in the potentially highly competitive forthcoming national elections in major cities should not be underestimated.

Frustration is growing among a segment of the public as concerns mount that student leaders may be attempting to exert full control over the interim government. It is crucial to recognise that the more they try to tighten their grip on the government and delay elections, the faster political parties will form alliances. As these alliances grow larger and stronger, student leaders may find themselves trapped in a political deadlock, potentially cornering the movement and compromising its objectives. To avoid this, student leaders ought to refrain from undue interference in the decision-making process of the interim government.

As the nation embraces new hope for state reform and enduring democracy, the advisers of the new interim government should exhibit more resilience, tolerance, and restraint in their interactions with the media and the public. This transitional government, led by the globally renowned Nobel laureate Dr Muhammad Yunus, was born out of the immense sacrifices of hundreds of students and the wider public. We must recognise that this is not a typical political government, nor is it a caretaker government like those seen in past decades. This government must stand as a beacon of hope and liberation for the people, who have endured years of deprivation and denial of rights under the AL regime.

The advisers of the transitional government must exercise greater sensitivity and prudence. They must avoid adopting the rhetoric of political leaders, which could compromise their integrity and invite controversy. Justice must be pursued diligently. Anyone accused of a crime should face the full extent of the law, but indiscriminate blame should not be cast upon any political party or group. Recent inflammatory statements by an adviser — such as threats to break someone’s leg for committing crimes or to shut down media outlets for perceived sycophancy — are not only inappropriate but dangerously authoritarian. We must remember that this government was born out of a collective struggle to dismantle a despotic regime and liberate the nation from autocratic practices. The aspirations of those who have fought so tirelessly for change should be evident in every action and demeanour of the government. Additionally, the involvement of a globally admired personality like Dr Yunus in the cabinet underscores the need to uphold both his esteemed reputation and the integrity of a government formed through such profound sacrifice. We must not let him fail and his government flop.

It has been observed that some of the advisers have displayed signs of frustration and exasperation when questioned about the interim government›s tenure. It is essential to understand that an interim government without a clearly defined tenure poses significant risks of ambiguity. Historical anecdotes illustrate that when a government lacks a clear timeframe and a concrete roadmap for institutional reform, it creates fertile ground for controversies surrounding its legitimacy and mandate. This ambiguity can breed resentment among the people, potentially leading to the failure of the movement’s broader objectives. To avoid such pitfalls, political consensus and national reconciliation are not just desirable — they are essential for achieving the state reforms that the people of Bangladesh so deeply aspire to. Without these, the movement risks fragmentation, making its goals increasingly elusive. Meanwhile, those with malicious intent are actively seeking to exploit any signs of instability. Although some of their plots have been foiled, the threat to both the government and the nation remains ever-present.

The interim government, political parties, and student leaders must come together without delay to initiate national dialogues aimed at reaching a consensus and fostering national reconciliation. This unity is vital for driving the necessary state reforms and rebuilding the nation from the ground up.

In conclusion, while the passion and energy of Gen Z have driven the movement to unprecedented heights, the next phase calls for a shift in strategy. Pragmatism, political consensus, and an inclusive approach that values the experience of seasoned politicians and the contributions of democratic political parties are central to ensuring that the noble goals of the anti-discrimination and state reform movements are realised. The journey ahead is long, but with wisdom and foresight, the movement can achieve the lasting change that Bangladesh so desperately needs.

Tanbir Uddin Arman ([email protected]) is a political analyst and commentator. He works with a Danish nonprofit organisation in East and Central Africa.

Leave a Reply